Many of you may not know that I have a deep love of art (and architectural) history. My passion for art grew exponentially when I took a course from the late Thalia Gouma-Peterson, professor of art history at The College of Wooster, in 1991.

The class was Women Artists 1940-Present, and wouldn’t you know that Thalia had pieces from her personal collection that she brought in to class and passed around: I recall caressing the curve of a sculpture from Elizabeth Catlett, marveling at the kinetic energy of a small Louise Bourgeois sculpture, tracing the lines of a Miriam Shapiro painting, and falling deeply in love with everything Louise Nevelson created. Those classes flew by in what felt like an instant — Thalia had a remarkable way of teaching that drew you in, captivating your imagination and not letting go until you walked back out into the weak Ohio sunlight, blinking, certain you’d just been on another planet entirely.

During a meeting with Thalia wherein we discussed the possibility of my helping her (as a teaching assistant), she called me a feminist. “Um, I’m not a feminist,” I replied rather meekly. Thalia squared her strong shoulders, sat up straighter and looked me in the eye. Burned through.

“Of course you are a feminist,” she said, her Greek accent thick with certainty. She laughed. “Deny it all you want, my dear. But you are a feminist.”

She changed my life that day.

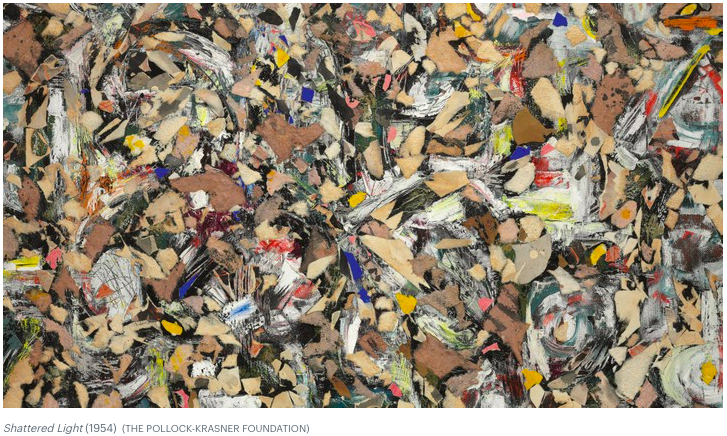

“Women Artists 1940-Present” also introduced me to the work of artist Lee Krasner, whose name was often synonymous with her husband, Jackson Pollack. A remarkable artist in her own right, Krasner’s work was frequently overshadowed by Pollack’s fame, but her contributions to modern art cannot be underestimated. Exploring the outer reaches of abstract expressionism, Krasner’s work had energy to spare, and I often found myself getting lost in her paintings. Unfortunately, her intense self-criticism and a near-obsessive tendency to revise and revise her work led her to burn or destroy many paintings and collages. Lucky for us she didn’t reduce them all to ashes.

This one, ‘Shattered Light’ (1954), is a favorite.

Which leads me to today’s #backpocketpost, a poem, “Regards for the inner light (L.K.).”

(In the 40s-50s, Krasner often left work unsigned, or used the genderless initials “L.K.” Typically in the 1940s and 1950s, Krasner also would not sign works at all, sign with the genderless initials “L.K.”. She also incorporated her signature into the painting itself, blending it until almost unrecognizable, as she did not want to draw attention to the fact that she was a woman or the wife of a famous painter.)

Lately I’ve been thinking of what Hans Hoffman, one of Krasner’s early teachers, said to her in 1937: “This is so good, you would not know it was done by a woman.”

(2020 reframe: This is so good, you know it was done by a woman.)

The poem that follows grew out of that comment.

Regards for the inner voice (L.K.)

Linseed-scented skin, bitten nails

fine wrists, hollows in places

few could reach,

she was not the climbing

or falling through

Brooklyn-born, Bessarabia-bred

she was the rising early

the first spark

the being pulled into

her forms not a likeness

but a flight in

And when she opened her doors

no language save collage

rushed out

cubist musings

on economies of ego

scissors at the ready

and half-day silences

thick with smoke after smoke

bread, then bourbon, the pigments

spread, the pendulum swings

work so good you would not know

it was done by a woman.

Contemplating

deliberate destruction

of what sits before her,

she pulls on a black coat

walks the creek bank

din of crickets and

inner critics rising and falling

like a dirge. Surrounding her,

pushing at her, 50s America

perfect and pure

so many pretty pictures

each one lacking a pulse.

Scenes but not events

like history without ruins

or vast museums built

to house the dull.

She returns to the studio

stokes the woodstove

and rips the canvas

from its frame. There is

no time like the past.

Let it burn.

Featured artist: The Still Tide